I, like many Black American women, grew up quilting with my mother and grandmother. It was just something we did as a family and a social activity. Plus, it was satisfying to decorate the house with items made by our hands. It wasn’t until later in life that I learned the rich history behind Black American quilting culture.

Culture of Black American Quilting

There is a rich and complex history that has been underrepresented in mainstream narratives for many years. Scholars, historians, and quilters themselves have been working to bring greater recognition to these contributions.

Enslaved women’s quilting traditions

Enslaved Black American women developed quilting skills both through necessity and as a way to preserve cultural traditions. They often worked with scraps and discarded materials, creating functional bedding for their families while sometimes incorporating African textile traditions and symbolic patterns.

Post-Civil War community building

After emancipation, quilting became an important social and economic activity in Black communities. Women gathered for quilting circles that served multiple purposes: creating necessary household items, building community bonds, and sometimes generating income through sales.

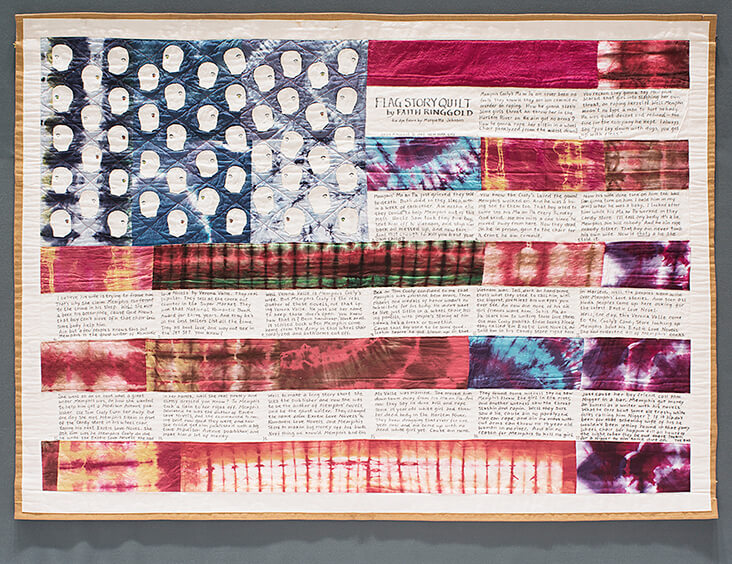

The Underground Railroad quilt code

There’s been significant discussion about whether quilts contained coded messages to help enslaved people escape via the Underground Railroad.

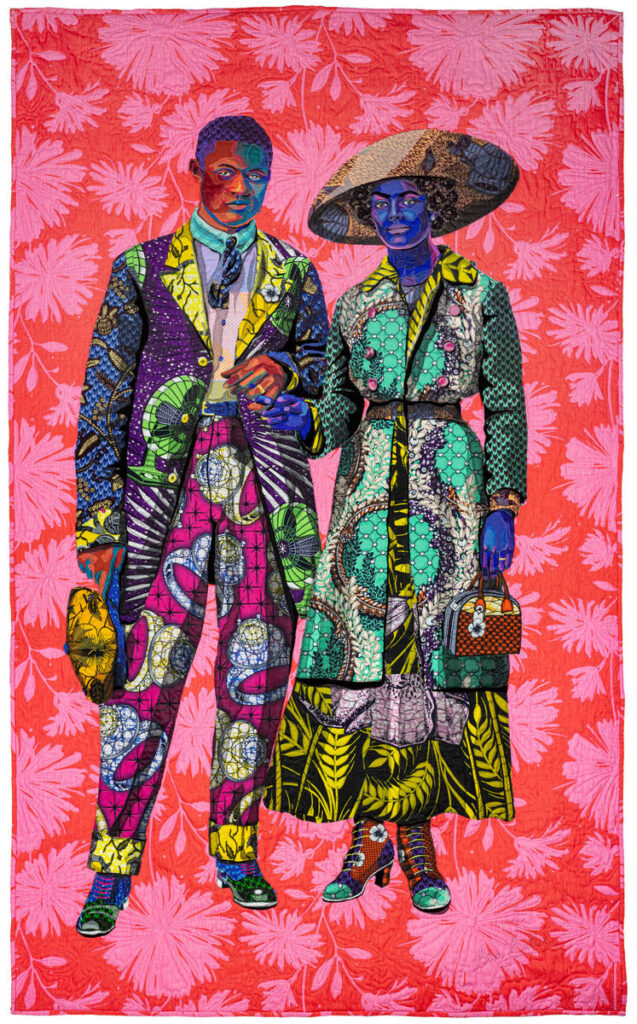

20th-Century artistic recognition

Black women quilters like the women of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, began receiving wider recognition in the art world for their innovative approaches to traditional quilting patterns. Their work is now displayed in major museums and recognized as significant American folk art.

Documentation efforts

In recent decades, there have been increased efforts to document and preserve the quilting traditions of Black American women through oral history projects, museum exhibitions, and scholarly research.

The challenge hasn’t been that this history was deliberately hidden, but rather that it was often overlooked by mainstream historical narratives that didn’t prioritize the domestic arts or the experiences of Black women.

Today, there’s much greater appreciation for how quilting served as both practical craft and powerful form of cultural expression and community building.

Iconic Women and Traditions

Harriet Powers, born enslaved, became a celebrated story quilter whose biblically-themed and historical quilts are preserved at the Smithsonian.

Lizzie Hobbs Keckley used her quilting skills to buy freedom for herself and her son, later becoming a renowned seamstress for Mary Todd Lincoln.

The Gee’s Bend quilters—a group of Black women in rural Alabama—created bold, improvisational quilts that gained international acclaim and are now in major museums.

Several contemporary Black women quilters like Laverne Brackens continue the tradition, integrating social commentary and honoring ancestral techniques.